While global commercial success eludes the region’s filmmakers, critically there have been a number of notable releases

This was not supposed to be a vintage year for Middle Eastern cinema. Mounting censorship, cutdowns in funding, and, most damagingly, low receipts have cast a shadow over the region’s cinemas.

And yet, with a mix of luck, fortitude and a credulous belief in independent film, Middle Eastern filmmakers pulled off a miraculous coup, producing a number of astounding works resulting in another exceptional year for a cinema that refuses to be trounced.

The post-Covid cinema climate has been perplexing and wholeheartedly unpredictable. The colossal success of Top Gun: Maverick and a few Hollywood blockbusters masked generally low turnout for smaller films.

With the Russian-Ukrainian war throwing the world into the steepest economic turmoil in a generation, the cinema experience has been deemed only worthy if it’s associated with event films.

A handful of mega Cannes hits such as the Palme d’Or winning satire Triangle of Sadness and the English family drama Aftersun have managed to conquer the congested art-house film market. But those crossover pictures are few and far between, and Middle Eastern cinema, like others, has struggled to push against the Hollywood machine.

Mainstream press has similarly turned its back on anything not Hollywood or Netflix, preferring to run the umpteenth piece on Hitchcock or Tarantino than giving space to new voices.

Streaming did provide a lifeline to some filmmakers, but it didn’t prove to be the financial nirvana directors were hoping for.

Middle Eastern movies came and went on Netflix and its ilk, with only scandal-addled pics like Farha garnering notoriety following Israeli calls for the film to be removed by the network.

Superior if less contentious Middle Eastern films failed to receive similar attention, proving once again that viewership is no measure for artistic quality.

As the shadow of the inflation and cultural homogenisation spread their ominous web on the Middle Eastern film scene, filmmakers continue to fight, exploring new forms, new methods of image-making, and new narratives in creating stories that have proven this year to be more urgent than their western counterparts.

Queer pics, hard-biting slices of life, political noirs, garish melodramas, monster movies, and bucolic dramedies…the diversity and inventiveness of the year’s best Middle Eastern film crop are a cause to celebrate. Together, they compose as an unruly mosaic reflecting a fervent engagement with contemporary politics.

The originality, emotionality and political audaciousness of the following 10 films rival the very best that came out from anywhere this year.

And for once, the abundance of notable Middle Eastern pictures this year has made it quite taxing to pick up only 10 films. Some other outstanding titles worthy of mention include: Saeed Roustayi’s Leila’s Brothers, Jafar Panahi’s No Bears, Ali Asgari’s Until Tomorrow and See You Friday Robinson from Iran; Ahmed Al-Daradji’s Hanging Gardens from Iraq; Philippe Faucon’s Les Harkis from Algeria; and Ehab Tarabieh’s The Taste of Apples is Red from the Golan Heights.

Most of these films will end up in one or more streaming platforms before the end of next year, but their natural homes remain the big screen, and they need to be shared with the biggest audience there is.

The longevity and survival of the Middle Eastern cinema remains dependent on you, dear reader, in seeking out these films in festivals and cinemas alike – in you pressuring your local theatre to screen them instead of waiting for them to drop with little fanfare on Netflix.

10. 19B

The sixth feature of Egyptian indie maverick Ahmad Abdalla is his most compact, most accomplished film since 2013’s Rags and Tatters.

A tense thriller centring on an old guard of a deserted villa whose tranquil, orderly existence is disrupted when a young, bullish hoodlum decides to invade the property.

The cat and mouse game that ensues is impregnated by a brilliantly subtle commentary on the gentrification of the old dying Cairo; on the lawless state of the marginalised classes, on the simmering violence of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s dog-eat-dog neo-liberal Egypt.

Highly entertaining and deeply engaging, 19B is one of the most politically potent Egyptian films of late.

9. Without Her

This list could’ve been exclusively made of Iranian titles. In spite of the crackdown on dissident filmmakers, detentions and expansive censorship – all in place before the September protests – Iranian directors have stood their ground and continued to find cracks in the system.

The result is arguably the strongest year for Iranian cinema in more than a decade. Arian Vazirdaftari’s debut feature is radically different from this year’s vastly eclectic crop: a Brian De Palma-like pulp noir about an upper middle-class woman who takes in an amnesiac girl only for the latter to start taking on her life.

A shrewd portrait of the relationship between class privilege and women’s freedom for self-actualisation, this Venice film festival contender is a superior piece of genre filmmaking, replete with ostentatious visuals, plot twists and nail-biting suspense.

And in the wake of the protests, its themes of the invisible domestication of women by a pervasive patriarchy have acquired a new-found meaning.

8. Ashkal

Hot on the heels of last year’s provocative rape revenge drama Black Medusa, Tunisian filmmaker Youssef Chebbi ups the stakes with his solo directorial debut, a noir thriller about two police officers investigating a mysterious series of self-immolations that may or not be concealed murders.

Shot in wide frames that accentuates the alienating relation of the characters to their disfigured and characterless post-revolution capital, the chosen setting of the Gardens of Carthage doubles as a metaphor for the return of the old despotic regime.

The luxury district was launched during the waning days of ousted President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali and development only resumed in recent years.

Peppered with supernatural elements, Ashkal is an imaginative and atypical reworking of the police procedural about the unhealed wounds of police brutality.

It also touches on the fading promises of the revolution and, most distressing, about an unchanged country drifting once again into autocracy.

7. Burning Days

The encroaching censorship and limitations of local funding are driving Turkish independent cinema into ruin, and 2022 bore witness to more scant representation internationally.

The existence of Emin Alper’s insubordinate fourth feature – which played at Cannes’ Un certain regard competition – has been deemed at first a near-miracle. But judging by the sudden demands of the government this month for the producers to repay its funding, it was clearly an accident – a glitch in the system.

A slow-burning thriller revolving around a young man who gets appointed as state prosecutor of a small conservative town ruled by an authoritarian mayor, the idealistic newbie finds himself in hot waters when his growing bond with the male editor of an opposition paper starts drawing ire from the residents.

An allegorical tale of governmental corruption, political opportunism and homophobia in rural Turkey, Alper’s best film to date is a perfect union between politics and genre, delivering a sharp blow to a regime that will think twice before bankrolling his future projects.

6. Harka

The directorial debut of American-Egyptian filmmaker Lotfy Nathan – which also bowed at Cannes’ Un certain regard – may appear on paper to be the most straightforward title in this list.

It centres on a familiar Tunisian anecdote about an an economically-strapped young man who finds himself saddled with the sudden burden of looking after his sisters following his father’s death; a burden made heavier with the obligation to pay debts loaded over their house.

In Nathan’s hands, what could’ve been another predictable yarn of post-revolution economic malaise is turned into an emotionally-charged, visceral tale of injustice, despair and the unbearable encumbrance of Arab manhood.

Powered by Adam Bessa’s astonishing performance and peppered with genre elements, the impeccably directed and superbly edited Harka is an austere, unsentimental look at Tunisia’s underbelly; a stern indictment of the flimsy post-revolution policies that failed to improve the conditions of the disadvantaged millions.

5. The Damned Don’t Cry

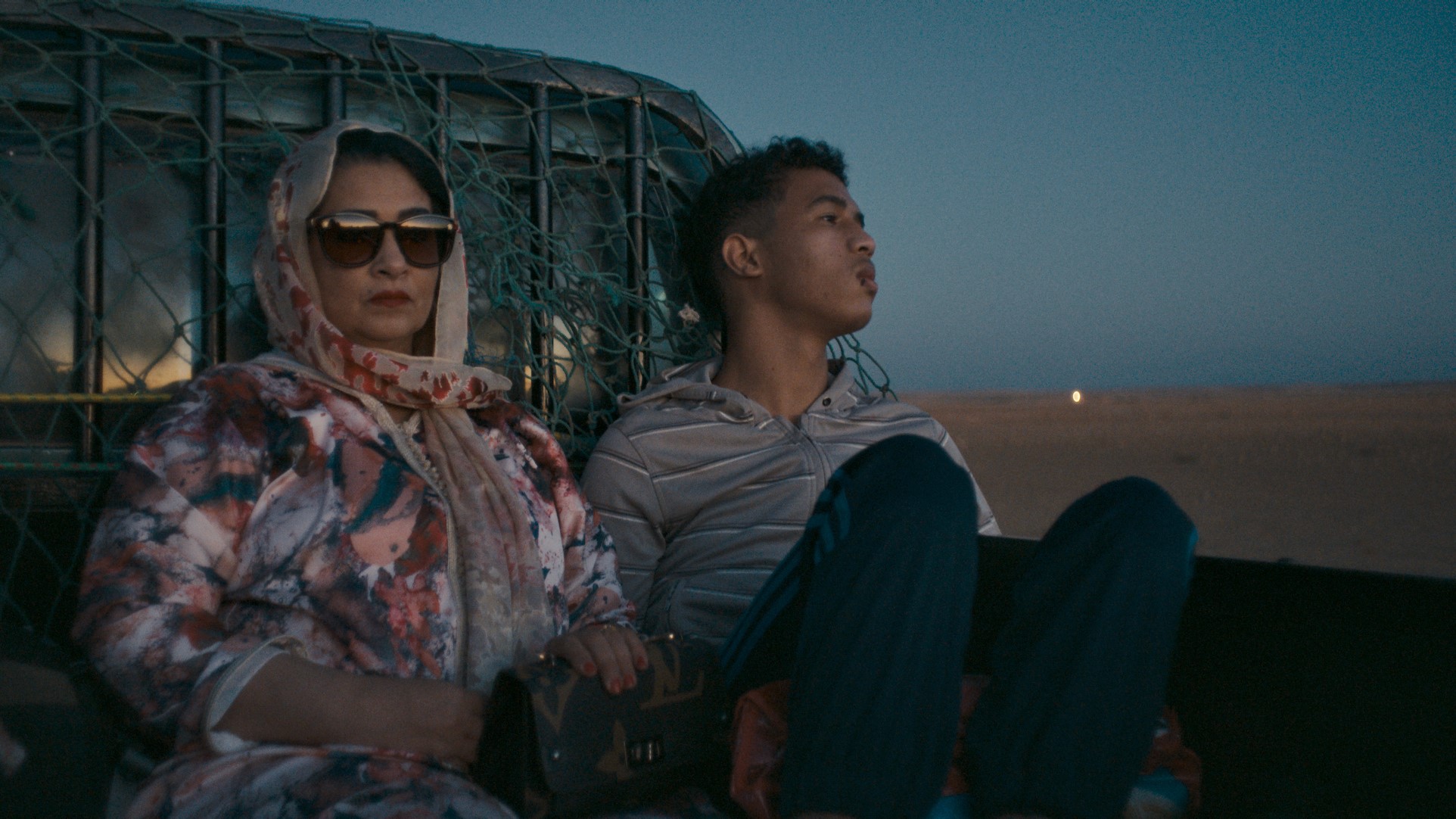

The second feature of British-Moroccan Fyzal Boulifa takes him to his parents’ homeland for this delectable tribute to Italian 50s melodramas.

Part a scorching mother-son relationship drama, part a queer coming of age story and part dramatisation of latent neo-colonialism, The Damned Don’t Cry, which premiered at the Venice Film Fest, is the most perverse, most dysfunctional Arab family drama of the year.

A scene-stealing Aicha Tebbae plays a retried sex worker who moves to Tangier in search of a fresh start as her sexually confused teenage son accidently embarks on an affair with his gay French employer.

Divergent in tone and sentiment to common Arab family dramas, the eponymous “damned” protagonists are not cursed by their class position or seemingly limited life options; Boulifa’s lovable friends are cursed by their imprudent choices, by their unbridled longings and their destructive love for one another.

4. Mediterranean Fever

Palestinian Maha Haj’s second outing is possibly the most formally unadventurous film in the list: a black comedy tracing the budding friendship between a depressed middle-aged aspiring writer and his new small-time racketeer neighbour in Haifa.

Admittedly, Haj’s cinema does little to inspire the eye, but what a staggering script the former Elia Suleiman collaborator has conjured up.

Remarkably fluid, deeply poignant and gripping from start to finish, Haj’s script – which won the best screenplay prize at Cannes’ Un certain regard – is a beautifully written, compassionately observed treatise on the indecipherable male bonding, on the protracted ennui of life under an unconquerable occupation.

It meditates on the desperate, painful search for meaning in a place where change is impossible.

Laced with aching resignation, Mediterranean Fever is the rare Palestinian film where humanism takes the upper hand over explicit politics; the rare Palestinian film demonstrating that the real damage of the occupation is not just the checkpoints or the apartheid or the settlements: it’s the fatal inward sense of futility.

One of the very best Palestinian films in recent memory.

3. The Blue Caftan

This has been a banner year for Middle Eastern queer cinema in spite of the burgeoning campaign against everything LGBTQ in the larger part of the region – a valiantly mutinous stance against tyrannical leaders exploiting conservative sentiments for political gains.

Of the various stellar queer pictures, Moroccan Maryam Touzani’s sophomore effort – which also premiered at Cannes’ Un certain regard – stands tall above the rest.

The Oscar-shortlisted picture is the Arabic Brokeback Mountain: a romantic tearjerker about a closeted middle-aged married tailor who falls for his new apprentice as his wife battles cancer.

Touzani chronicles the thwarted romance of the two men with affecting delicacy and sensitivity without sanitising their repressed sexual hunger.

Anchored by a career-best performance by Palestinian thespian Saleh Bakri and Lubna Azabal of Incendies fame, Touzani’s classical story is played out in a series of close-ups that emphasises the tactile, the physical and the unspoken.

Commendably steering away from fatalism, Touzani’s nuanced, hopeful and incredibly moving tour-de-force is possibly the first Arab queer classic of the decade.

2. The Dam

The directorial debut of renowned Lebanese visual artist Ali Cherri is the boldest, most visually intelligent Middle Eastern film of the year; a striking monster story unlike anything made before in the long history of the region’s cinema.

Set against the backdrop of the 2018 Sudanese revolution, a lonely bricklayer (played by real life bricklayer Maher El Khair in his first screen performance) channels his alienation and confusion into setting up a secret gigantic mud construction which steadily comes to life.

Largely unfolding in still frames with nearly no dialogue, Cherri’s art background is palpable in every shot: from the truncated bodies positioned in relation to their desolate surrounding, to the emphasis on the physicality and repetitiveness of manual work.

Most impressively is his wide-ranging palette whose disparate references range from pre-Islamic Arab culture to Frankenstein.

The Dam’s uniqueness, however, lies in how Cherri perceptively marries the political with the personal via the fantastic.

Exact and unwavering in its vision, The Dam – which premiered at Cannes’ Directors’ Fortnight sidebar – is both a political fable and a powerful existential study on the elusive meaning of freedom; a rich impressionist portrait of a nation and a people on the cusp of unknown change crafted with great mastery by one of the most exciting new voices in Middle Eastern cinema.

1. Under the Fig Trees

The Tunisian countryside. One summer morning. A group of young women farmers in their countryside are picked up by a foreman at early dawn as they make their way to a fig ranch.

They settle in the orchard, talk, pick up the figs as gently as instructed and avoid committing the irredeemable blunder of breaking the branches. They take breaks, eat, flirt with the foreman, scrutinise their surroundings and gossip.

Everything and nothing occur in Erige Sehiri’s second full-length feature and first fiction – a partially-improvised, tension-free drama with no narrative or plot, fronted by a cast of non-professional actors from the countryside.

Yet over the course of that one uneventful day, Sehiri opens up a window to the unknown and seldom documented world of the Arab countryside that upturns the stereotypical and dated misperception of the village life; a gorgeous, sun-kissed enclave populated by determined, loud, desirous women in love with themselves and each other.

There are sprinkles of power dynamics that figure in on occasion, augmented by the girls’ dissimilar mores and dreams, but Under the Fig Trees is, first and foremost, a sensory experience: an engulfing Renoiresque celebration of life, womanhood and the quotidian.

Shot on a shoestring budget partially during the pandemic, Sehiri’s modern masterpiece has been enchanting viewers the world over since its debut at Cannes’ Directors’ Fortnight – from Toronto and Melbourne to Rio de Janeiro and Marrakech.

This is pure movie magic – a film made with a lot of love for both the director’s subjects and cinema itself. Under the Fig Trees is the most life-affirming Arab film of the year, and the most joyful 90 minutes this writer has spent at the movies in 2022.

Special mention: Warsha

Dania Bdeir’s Beirut-set queer pic made headlines for winning the Short Film Jury prize for best international film at the Sundance Film Fest.

A firecracker of grandiose images set against Umm Kulthum’s epic Al-Atlal, Warsha is a gorgeously-lensed snapshot of a gay Syrian migrant working on a construction site who finds the freedom to realise his identity on top of a forebodingly gigantic crane.

Warsha’s real significance is in its appropriation of Arab pop cultural artefacts – namely the aforementioned Umm Kulthum anthem and the garish customs of Egyptian 80s dance icon Sherihan – into a new queer context that can only be identified and fully grasped by Arab viewers.

Refraining to spoon-feed these cultural signifiers to the western viewer, Bdeir’s Oscar-shortlisted gem is the best Arab short of the year: a work of great integrity that breathes new life to an Arab cultural heritage the West remains oblivious to.

Source : Middle East Eye